|

|

| Feedback |

|---|

Real Resources Review: A little makes a lot?I sent John Busby's 7th August article to a friend who understands more about nuclear power than I do. His reaction was that 'Mr Busby is not conversant with the concept of pebble bed reactors'. I would like to ask Mr Busby how he views that technology and whether he would care to tackle it in an article for the uninitiated like myself? Kind regards, Paddy Imhof

The problem is that mining of uranium is running down, whatever form of reactor is envisaged. See Die Welt which reports the imminent closure of some of the French reactors due to fuel shortages. The thorium alternative and fast breeders are dependent on vast development programmes which with the rapid and progressive failure of the nuclear industry will never be funded. As far as the pebble bed reactor is concerned it depends on the integrity of the pebbles and as these contain graphite this is likely to lead to the demise of this technology. The seven UK AGR's are likely to close prematurely as the graphite moderator blocks are disintegrating due to the irradiation which causes structural breakdown. Also there is an overheating due to the Wigner Energy effect which leaves a residual heat in the graphite. The gas-cooled fast reactor is also an unlikely candidate for funding for this reason as it relies on graphite moderation. The nuclear lobby in desperation is arguing that uranium can be extracted from the earth's crust and seawater and looks to fast breeders to generate ever more plutonium. All of which is fantasy. We do not have to wait too long for some of the

lights to go out in France, which will hopefully lead to a reality

check! |

| Is the Sun Setting on the U.S. Military Empire? |  |

|

| By Jon Rynn | |

| Jun/01/2006 | |

|

Some nations rise, turn into empires, destroy themselves from within, and fall. The U.S. is no exception. When the empire of the Soviet Union collapsed, the U.S. faced an exceptional situation – the Great Powers of 1991, for perhaps the first time in history, were not threatening each other. But instead of dismantling the huge military-industrial complex of the post-World War II period, the colossus grew unabated. . . Great Power destroys great manufacturing, and so, in the long-term, Great Power destroys itself from within. . . Any centrally-planned economy will turn into a military economy; a military economy cannot exist without its necessary partner, central planning. The jackals of the U.S. power elite gathered, stole an election, and when Al Qaeda struck, the neoconservatives in power jumped at the chance to use that which had just failed, the Department of Defense, for their own imperialistic ends. The common thread linking the British, American, and Soviet experiences is the rise of their respective military institutions and attendant military empires. These attracted more and more capital, both financial and human, to the detriment of the manufacturing bases that made the military efflorescence possible. There would have been no British Empire without the British-led industrial revolution; the sun set on the British Empire because the sun was earlier setting on the British manufacturing system. Great Power follows great manufacturing . The Soviet Union from the 1930s on, Japan after World War II, China today – they would not have been so important were it not for all of their accomplishments in manufacturing.[1] And yet, eventually, Great Power destroys great manufacturing, and so, in the long-term, Great Power destroys itself from within.

When a military-industrial complex arises within a Great Power, it replaces the machinery, manufacturing and infrastructural sectors as the destination for the best finance and human capital. This process was at work in the past in the Soviet Union and is presently eating away at the United States. The Soviet Union was basically one big military-industrial complex. Its best and brightest were drawn into, or forced into, military production. The Soviet Union was centrally planned, not to help the working class, but in order to build a military-industrial complex. A military economy is a centrally-planned economy, and vice versa. Any centrally-planned economy will turn into a military economy; a military economy cannot exist without its necessary partner, central planning. How the Soviet Empire rose…

Hitler, on the other hand, was very unimpressed by the same effort, and keyed his entire military strategy to avoiding a total war economy, because he thought that the Kaiser lost support at the end of World War I because the population suffered too much from the collapse of their economy. The advantage of the blitzkrieg, developed by the British military historian Liddell-Hart,[3] was not only that it led to military victory, but that it also was much less taxing for the aggressor’s population. Unlike Hitler, however, Lenin did not have the luxury of sitting on top of the world’s second strongest industrial base. He had to create one. When the Bolsheviks had to fight a civil war to establish their rule, Trotsky created what he called a “war communism”, allegedly temporary, that required as much planning as possible, over as much of the economy as possible, in order to funnel as much of the country’s economic activity as possible into the military effort. The strategy succeeded, the Bolsheviks solidified their rule over the entire Russian Empire, and the Soviet Union was born. After this period of total control, Lenin loosened the reins over the economy in the form of the New Economic Program, which gave a fair amount of independence to private firms. But during the late 1920s, a debate raged, although quite civil by later standards, as to how best to industrialize the Soviet Union. The consensus achieved by the Soviets was that an economy is composed of a manufacturing core, centered in turn on a core of production machinery, or as it is sometimes called, a capital goods sector. In order to industrialize, an industrial system and capital goods sector must be constructed. This is very similar to my explanation of the workings of a modern economy as elaborated in “Before the Economy Hits the Fan”, although there are some differences. Marx, in the third book of “Das Capital”, conceptually divides an economy into a Department I, which produces consumer goods, a Department II, which produces the goods that produce the consumer goods, and a Department III, which involves creating the additions to the capital goods sector, that is, Department II. This insight was elaborated by a Soviet economist named Feld’man,[4] and Stalin himself seems to have had a profound understanding of the meaning of this conception of the economy. Thus, an industrial core of an economy must be constructed in order to create the rest of a wealthy economy. One would think that this insight would be considered rather obvious by economists. For people living in the middle of the second industrial revolution, in the 1920s and 1930s, who could see the new kinds of machinery and products being churned out every day, this was very clear. But for economists like those in the present-day U.S., where financial manipulation and global corporate empires are the order of the day, it is an uphill battle to try to argue for the centrality of manufacturing and production machinery.

By the end of the second Five-Year plan, in the 1930s, the Soviet Union had constructed enough universities to pump out enough engineers, and enough technical institutes to produce enough skilled production workers, and enough electrical plants and steel plants and machine tool factories that they could tell the American and German engineers to go home. Armed with a huge industrial apparatus that could be used to generate more of itself, Stalin could divert some of his industrial capacity to create a military force that could repel the next invaders. …And how the Soviet Empire fellRepel the Germans they did, which would have been impossible had they not created an integrated industrial base in the 1930s. Thus, by understanding the importance of manufacturing and machinery, it is possible to explain the rise of the Soviet Union. We can also use this framework to understand the fall of the U.S.S.R. Germany, the rest of Europe, and Japan were destroyed at the end of World War II. The only other possible industrial power by 1945 was Britain. It is inaccurate to say that Britain lost its Great Power status because it was “bled white” by two world wars, as expensive as they were. Germany and Japan recovered after much worse destruction and expense. Great Britain emerged after World War II as America’s “poodle” because the British “Workshop of the World” had turned into the British Empire. With both the workshops and Empire gone, there was nothing left to support its claim to Great Power status.

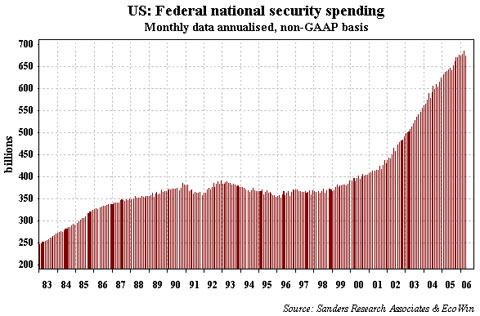

What the term “heavy industry” obscured, however, were the seeds of Soviet collapse. Heavy industry refers to both military industry and capital goods production. Had the Soviets concentrated on the industrial core, there would have been something to worry about. Instead, by 1980, by the estimates of some Soviet economists, the Soviet economy had actually crossed the line from zero growth to negative growth, and was getting worse.[6] The industrial base was critically ill; the machinery industries had been starved of capital,[7] while the military industries had been lavished with whatever riches they desired. According to one estimate, fully 80% of industrial capacity went towards the military economy by the 1980s.[8] Gorbachev’s economic program, which was virtually ignored in the West, was to rebuild the machine tool industry back up to world class levels.[9] The understanding of the importance of the industrial core had not completely disappeared, but it only reasserted itself as a kind of end-of-empire Ghost Dance. The rise and fall of the Soviet Union can be explained if one understands the importance of the manufacturing and machinery sectors. When the Soviets built these sectors up, it became the second most powerful state in the world; when they diverted resources to the military and ignored their civilian machinery, the empire collapsed. Following in the U.S.S.R’s footstepsThe United States is in a remarkably similar structural situation today, even if the circumstances are somewhat different. The military-industrial complex of the United States is the largest single planned economy in the world. The procurement budget for fiscal year 2004-2005, the most recent data available, was $269 billion.[10] The total for military expenditures, according to the CIA, was $518 billion in fiscal year 2004-2005.[11] According to the website GlobalSecurity.org, the total military expenditure outside the U.S. in 2004 was $500 billion,[12] so the U.S. has the dubious distinction of spending more on the military than the rest of the world combined. In addition, private corporations are also hollowing out the manufacturing base by outsourcing manufacturing (and even services) to other countries, as I showed in “Say Dubai to the American Economy”. The consequences of spending on the military-industrial complex are greater than the number of dollars spent. The state has always had a fundamental effect on the nature of the economy because of the way it spends money. When the state declares a particular sector to be on the “commanding heights” of the economy, it showers that sector with resources, and the best and brightest engineers, scientists, and skilled production workers flock to be part of the gravy train.

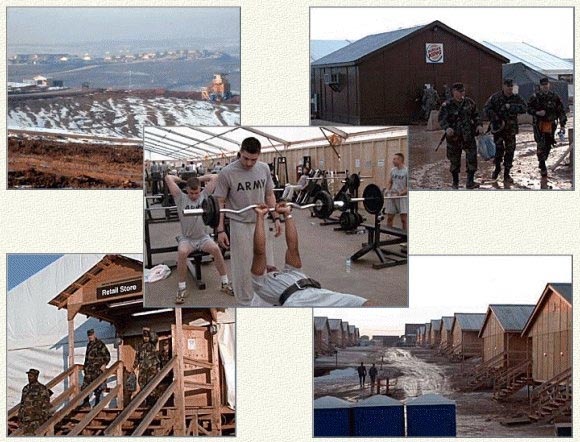

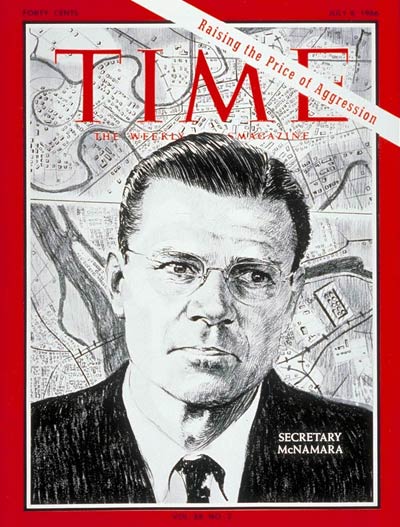

In premodern (and sometime modern) times, roads, canals, and irrigation played the role of helping the rest of the economy gain competence in various technologies through government largesse. The Japanese, through MITI, targeted particular industrial sectors at certain points after World War II.[14] Each time the sector was “guided” by MITI, it vaulted to the top tier of world competitiveness; for instance, in the 1970s the production of semiconductor-making equipment was organized, and Japan now leads the world in this strategic industry. Besides the expense, the second major bad habit learned from military production is that machinery is designed that is too complicated for sustained, reliable use. Not only is the production of the equipment more expensive than it should be, the maintenance required to keep the equipment operating is much greater than is conceivable in a civilian market. Civilian firms, drawn like moths to light, try to obtain as many military contracts as possible, and by so doing destroy their own competence and contribute to a weakening of competence within the economy as a whole. The program of the Politburo of the Republican PartyThe great irony of the American political landscape is that conservative Republicans, who worship the “free market”, are determined to expand the central-planning agency of the United States. The logic of their arguments would lead to the following scenario, which would be so similar to the Soviet Union, that it is possible to equate the American conditions to the Soviet example to forecast an American collapse, QED. According to the conservative logic, virtually the entire Federal budget should be devoted to the military. Currently, the U.S. military has 700 bases worldwide; why not have one thousand, complete with swimming pools and golf courses?[16] After all, 14 new bases are being built in Iraq alone. As in the Soviet case, the military bases and facilities treat their occupants to a grand life-style, while civilians outside of the military sector get by on worse and worse left-overs. Conservative logic would probably lead to a virtual open border, with millions more immigrants, on the verge of starvation because of NAFTA and other free-trade policies, bringing wages down to about survival levels, with virtually no health insurance or other safety net. This might push the less-educated, poorer part of the native American working class into the arms of U.S. militarists, and provide cannon fodder for more wars, another conservative/neocon goal. Conservatives keep pushing for more underpaid hi-tech workers to be allowed to work in the U.S., a situation rife with exploitation because these workers can be expelled from the country if their host company fires them. The working and middle classes of the U.S. would virtually disappear if the conservative ideologues had their way because lower wages are mistakenly claimed to lead to greater “competitiveness”. Meanwhile, with no regulation of corporate behavior or trade into the U.S., the outsourcing of jobs, production competence, and whole companies abroad could continue apace. The conservative dogma continues to claim that trade deficits don’t matter. With no concern for global warming, a crumbling infrastructure, or a dangerous reliance on a dwindling supply of petroleum, the U.S. would be prone to worse-than-Katrinas and a situation in which conservative voters would be stuck in their suburbs and SUV’s trying to survive on $20/gallon gasoline. With the industrial sector more and more made up of only military industry, with no way to pay for imports, with a low-skill workforce in bad health, the U.S. would be set up to experience the collapse of its currency and economy in the same way as Russia in 1990s, perhaps as extreme as the collapse of 1998. Except that the U.S. doesn’t even have an oil and natural gas sector to claw its way out of depression. The only asset left to the U.S. would be a huge military sector. We have seen how that has been playing out in the fiasco of Iraq. Once a huge military sector has been established, the public, even one as oppressed as in the Soviet Union, need some legitimation for such a colossal waste of resources. During the Cold War, the Soviets could scare the population with the threat of Capitalist invasion just as the U.S. could scare its population with the threat of the Communist menace. Once the Cold War was over, the military was still remarkably successful in maintaining its funding. Apparently it had done such a good scare job in the previous 40 years that it didn’t even need much of a threat to maintain itself. The problem is that when in possession of a huge military apparatus, the “deciders” are not always content, as Clinton was, to simply tread water; as Rumsfeld, Cheney, and others made clear from their perch at the Project for a New American Century in the 1990s, they wanted to use this new imbalance of power to greatly expand their own power.[17] The days of the jackalsOn September 10, 2001, Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld announced that the Pentagon could not account for $2.3 trillion, that the money was missing.[18] On September 11, the neocons found a justification to spend many more trillions of dollars, and with little oversight to boot. By 2:40 pm that day, Rumsfeld was talking about invading Iraq, and on September 12, Bush and Rumsfeld were pressuring Richard Clarke to agree.[19] It is not necessary to argue that the neocons planned 9/11 to understand the dynamics at work. In referring to the Bush administration, I used the term “jackal” in the opening paragraph for a reason; unlike lions or other predators, scavengers wait for someone else to do the dirty work, and then they move in. Unlike jackals, the neocons do not perform a useful function by scavenging, they serve to further the destruction created by others. Our modern-day jackals are so far degenerated that they cannot even construct a proper empire. As I said before, Hitler used blitzkrieg to minimize the use of resources during war. But blitzkrieg as a device for empire-building requires more than the “lightning” movement of mobile forces to envelop and capture the enemy. When Hitler destroyed France’s military, he was careful to co-opt and use the French bureaucracy, because to have an empire means that one must govern the provinces. Instead, Rumsfeld’s consul, L. Paul Bremer, disbanded the Iraqi bureaucracy, leading to the present chaos. As Naomi Klein makes clear, the neocons were so greedy that they wanted to buy up the Iraqi economy, and effectively, enslave the Iraqi people.[20] They didn’t even understand that your typical would-be emperor needs a government that can control the people, even at the expense of some short-term profits. They probably don’t know this because they are so poorly educated. Those who do not learn from history are doomed to making worse and worse mistakes. The Neocons and Bolsheviks had diametrically-opposed views of the world: one celebrating markets and elites and the other pro-state-planning and, allegedly, pro-working class. But they both shared one passion that leads to social destruction -- in capitalist society or communist -- the deification of the military. The final stage of a star’s life occurs when its fuel starts to give out. The core of the star starts to collapse, but the lighter layers of the star turn red and expand to swallow up any planets that may be surrounding it. The star turns into a red giant, but soon (in astronomical time), it will lose its red outer layers, and either collapse into a white dwarf or explode as a nova. Like a red star, the U.S. looks strong now because of its large military and percentage of world GDP. The previous red star, the Soviet Union, collapsed into a set of economic dwarfs. Many breathed a sigh of relief that, unlike many declining Great Powers, the Soviet collapse was not accompanied by a supernova of military expansion. Humans have greater control of their societies than a star does, but the sooner the U.S. confronts its problems, the better the chances that its sun will set peacefully and not explode.

You can contact Jon Rynn directly on his jonrynn.blogspot.com . You can also find old blog entries and longer articles at economicreconstruction.com. Please feel free to reach him at This email address is being protected from spam bots, you need Javascript enabled to view it . [1] See the first chapter of my dissertation, “What is a Great Power”, at http://www.sandersresearch.com/www.economicreconstruction.com [2] For the best discussion of early Soviet economic policy, see Alec Nove, An Economic history of the USSR: 1917-1991, Third Edition, London:Penguin Books, 1992. Also see William Blackwell, The Industrialization of Russia: An historical perspective , Second edition,1982. Much of the material about the Soviet Union was presented by the author in a paper entitled “The Rise and Fall of The Soviet Union”, at the New York State Chapter of the American Political Science Association, 1995 [3] See his classic, B.H. Liddell Hart, Strategy, Second Revised Edition, 1991. [4] See "A Soviet Model of Growth," in Evsey D. Domar, Essays in the Theory of Economic Growth , New York, Oxford University Press, pp. 223-61, 1957. [5] Von Laue, Theodore H., Why Lenin? Why Stalin? Why Gorbachev?, Third Edition, p. 147-48, 1993. [6] Anders Aslund, “How small is Soviet national income?”, in The Impoverished Superpower, ed. Henry Rowen and Charles Wolf, 1990. [7] For a compelling discussion, see Nikolai Shmelev and Vladimir Popov, The Turning Point, 1992. [8] Alexander Belkin, “Needed: A Russian defense policy”, Global Affairs, Fall 1992. [9] The Rand Corporation did a study of this phenomenon, but a CIA history of their analyses of Soviet economy points to the following reference, Matosich, Andrew J. “Machine Building: Perestroika’s Sputtering Engine”, Soviet Economy , 4, No. 2, April-June 1988, 144-78. [10] http://siadapp.dior.whs.mil/procurement/2005_data/dod/summaryDoD200509.pdf [11] http://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/geos/us.html , Military section [12] http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/spending.htm [13]

Source:

Sanders Research Associates. The costs represented by the chart for

total National Security Spending includes in addition to the direct

costs incurred by the Department of Defense spending for energy,

international affairs, general science, space and technology,

veterans benefits and services, and administration of justice (these

are the line item labels used by the US government). They do not

include emergency supplemental appropriations for the wars in Iraq

and Afghanistan, which in 2005, for instance, totalled $76 billion

and so far in 2006 have totalled $49.9 billion. For FY 2003 and FY 4

these were $78.6 billion and 88.1 billion respectively (Source:

Congressional Budget Office, The Budget and Economic Oulook, Fiscal

Years 2007 through 2017, Box 1-1). These figures themselves do not

include spending for “coalition support” or classified activities.

[14] The classic work is Chalmers Johnson, Miti and the Japanese Miracle, Reprint Edition, 1983. [15] For example: In the Grip of Permanent War Economy, and other articles on the website aftercapitalism.com, as well as, most recently, the book After Capitalism, Alfred A. Knopf, 2001. [16] For a compelling discussion of America’s empire, see Chalmer’s Johnson, The Sorrows of Empire, 2004. [17] Available at http://www.thefourreasons.org/PNAC/RebuildingAmericasDefenses.pdf [18] http://www.defenselink.mil/speeches/2001/s20010910-secdef.html , quoted by Seymour Melman in his unpublished book, War Inc., 2004. [19] The full text is available here [20] Naomi Klein, “Baghdad Year Zero: Pillaging Iraq in pursuit of a neocon utopia”, Harper’s Magazine, September 2004. |

|

| Register Free to receive updates of latest stories |

|---|

| Polls |

|---|

In the Soviet case, the

word “communism” should be seen as a shortening of the term “war

communism”. Lenin, and the Bolsheviks in general, were baffled as to

how to create a socialistic economic order in the new Soviet Union

for one very good reason: Marx never laid out an alternative to the

object of his life’s work, capitalism. The term “dictatorship of the

proletariat” is not a very large peg on which to hang a plan to

industrialize the heart of the Eurasian continent. During World War

I, as it turns out, Lenin was cooling his jets in Germany, and he

was very impressed by the planning apparatus that was set up by the

Imperial government in order to run a total war economy.

In the Soviet case, the

word “communism” should be seen as a shortening of the term “war

communism”. Lenin, and the Bolsheviks in general, were baffled as to

how to create a socialistic economic order in the new Soviet Union

for one very good reason: Marx never laid out an alternative to the

object of his life’s work, capitalism. The term “dictatorship of the

proletariat” is not a very large peg on which to hang a plan to

industrialize the heart of the Eurasian continent. During World War

I, as it turns out, Lenin was cooling his jets in Germany, and he

was very impressed by the planning apparatus that was set up by the

Imperial government in order to run a total war economy.

Such obfuscations did not

concern Stalin as he was consolidating power by 1930. As he

explained in a famous speech at the time, the Russians had been

constantly invaded by more powerful neighbors, and, he explained,

the Soviets had maybe ten years to telescope 100 years of industrial

advancement in order to face the next set of invaders -- Germans,

probably.

Such obfuscations did not

concern Stalin as he was consolidating power by 1930. As he

explained in a famous speech at the time, the Russians had been

constantly invaded by more powerful neighbors, and, he explained,

the Soviets had maybe ten years to telescope 100 years of industrial

advancement in order to face the next set of invaders -- Germans,

probably. After 1945, Stalin could

have converted his now total war economy back into a very successful

industrial core. The West trembled in the 1950s because they thought

that the Soviets were capable of prioritizing the machinery sectors,

and there was a realization that a country that could nourish and

focus on “heavy industry” could outcompete a market-based society

that diverted so much of its output to waste. By the time of

Sputnik, a full-scale hysteria developed.

After 1945, Stalin could

have converted his now total war economy back into a very successful

industrial core. The West trembled in the 1950s because they thought

that the Soviets were capable of prioritizing the machinery sectors,

and there was a realization that a country that could nourish and

focus on “heavy industry” could outcompete a market-based society

that diverted so much of its output to waste. By the time of

Sputnik, a full-scale hysteria developed.

The Soviets and U.S.

governments warped their industrial systems by rewarding skill at

making military equipment. Production for war has always been rife

with corruption, creating profit for guns that don’t work and

ammunition that doesn’t explode. But even more harmful are the

habits of production that are inculcated in those who create

instruments of destruction, as Seymour Melman showed in a lifetime

of scholarship.

The Soviets and U.S.

governments warped their industrial systems by rewarding skill at

making military equipment. Production for war has always been rife

with corruption, creating profit for guns that don’t work and

ammunition that doesn’t explode. But even more harmful are the

habits of production that are inculcated in those who create

instruments of destruction, as Seymour Melman showed in a lifetime

of scholarship.